The Choir Bouncing on Bars

At a rehearsal with the Philharmonie der Universität Wien, I experienced the strangest kind of failure. The choir was not wrong. Every entrance was technically in place, the rhythms aligned, the notated values observed. Yet the music refused to breathe. Instead of unfolding as a phrase, it bounced. Each voice seemed to fall obediently into the downbeat, then lurch toward the next, as if tethered by invisible cords that snapped taut at every bar line. I found myself conducting not music but punctuation, a series of jolts instead of a line.

In that moment I realized that the singers were not following me, nor even listening to each other. They were following the score’s vertical divisions. The bar lines, those faint stripes meant to clarify the page, had usurped the role of the music itself. The choir was marching across a grid instead of singing through time.

This is what I call the tyranny of the bar line. On paper, it looks innocent, a neutral slash demarcating rhythm. But in practice it exerts a gravitational pull that shapes how musicians think, rehearse, and perform. What was originally invented as a tool of orientation has hardened into an authority of its own.

The Promise and the Violence of the Grid

The bar line is a late arrival in the history of notation. Medieval chant flowed without it. Renaissance polyphony, though measured, treated lines as light scaffolding. It was only with the rise of large instrumental ensembles that measure became indispensable. When you are trying to align a hundred musicians across a symphonic stage, the bar line is a miracle: a common ruler, a shared pulse, a guarantee that downbeats fall together even when everything else differs.

And yet, as with every miracle, there is a cost. Bar lines divide what is meant to flow. They chop the arc of a melody into equal compartments, like drawing boxes across a river. The page looks cleaner, but the current resists. Every singer knows the sensation of running out of breath not because the phrase is long but because the bar insists on an artificial stop. Every pianist has wrestled with a Chopin phrase that refuses to land obediently at the end of a measure. Every conductor has faced an ensemble that plays “correctly” but without line, because the score’s vertical strokes have been mistaken for the shape of time itself.

The paradox is simple: we cannot dispense with bar lines. Without them, rehearsal collapses into chaos. But the more faithfully we obey them, the less music we make. The grid is indispensable, and the grid is destructive. This contradiction lies at the heart of modern performance.

Hindemith and the Lark

Paul Hindemith once wrote that while human action can be measured against the clock, it does not respond to it in the way musical material does to its “millimetric paper.” It is a striking image: a page of staff lines as a kind of graph paper, a surface onto which sound is forced, squared, and straightened. The remark contains both resignation and defiance. Yes, we need the paper. But no, the paper is not the truth.

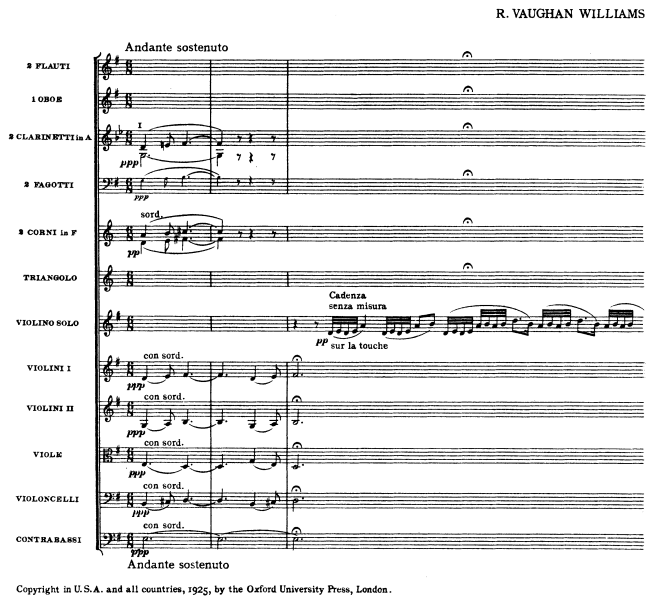

This tension is made visible in one of the twentieth century’s most beloved works: Vaughan Williams’s The Lark Ascending. In many editions, the solo violin line is written without bar lines. The orchestra below ticks dutifully along in measured compartments, but the lark sings freely above them, as if ungridded. The effect is revelatory. You can see, even before hearing, that music does not belong to the boxes. The bar lines are there to serve the ensemble; the solo line proves they are not intrinsic to the act of singing.

I often think of this when facing a page in rehearsal. Music plotted in square boxes is no more “real” than a bird confined to a cage. The bars help us rehearse. They do not help us fly.

Conducting Against the Grid

The practical problem, of course, is that musicians are trained to trust the page. Their eyes fall naturally on the bar lines, and their bodies feel the pull of the downbeat. To resist that force is almost unthinkable, like asking a runner to stride past the finish line instead of stopping where the chalk dictates.

This is where conducting becomes less a matter of beating time and more a matter of bending it. In rehearsal I rarely tell singers to “ignore the bar lines”, the command would only tighten their grip on them. Instead, I breathe differently. I shift my body forward, shaping gestures that transmit phrasing rather than beat. Sometimes it is the softening of a hand, sometimes the visible exhalation before an entry, sometimes simply the refusal to give a vertical cut where the score insists on one.

The results are never immediate. Ensembles resist, though not consciously. The pull of the bar is like the pull of gravity; it takes time to unlearn obedience. I have felt choirs snap back into the measure even when my whole body pleaded otherwise. I have seen orchestras land a phrase safely on a bar line even when the composer clearly wanted it to spill past. The problem is not laziness or misunderstanding. It is faith. The symbol on the page has acquired more authority than the sound in the air.

The truth, I have come to realize, is both blunt and liberating: bar lines are necessary, but they are overrespected. They are scaffolding mistaken for the building itself. My role as conductor is not to abolish the scaffolding, that would be impossible, but to constantly remind musicians, by gesture and by breath, that the building lies elsewhere.

Beyond Music: Grids of Life

This is not only a musical problem. The tyranny of the bar line echoes through every domain where human life is organized by approximations. Bureaucracy, schedules, standardized forms: they exist to help us coordinate, to live together in ordered systems. And yet we often mistake them for reality itself.

We see it in the office worker who believes they can only act within the template designed by someone else, even when their situation demands improvisation. We see it in citizens who treat bureaucratic paperwork as more binding than the lives it purports to describe. We see it in education systems that reward fidelity to the rubric rather than the depth of understanding. In every case, the grid designed to assist us ends up constraining us.

The bar line is simply the musician’s version of this broader condition. It is the reminder that most systems of reference are approximations, useful but incomplete. To live entirely within them is to confuse the map for the terrain, the scaffolding for the structure, the measure for the music.

Living in Contradiction

When I think back to that choir at the Philharmonie, bouncing obediently from downbeat to downbeat, I realize that what I witnessed was not just a rehearsal gone stale. It was a microcosm of how easily we surrender to symbols. The singers were not lazy, nor untalented. They were overfaithful. They respected the bar line more than the phrase.

And when I remember the opposite moment, the time I stopped conducting beats and simply breathed with the choir, letting the line emerge unforced, I see the other half of the contradiction. The bars did not disappear. They remained on the page, necessary for coordination. But they no longer defined the music. By breathing, we loosened their grip.

This, for me, is the enduring lesson: bar lines must be kept, and bar lines must be resisted. Without them, chaos. With them, tyranny. The only way forward is to inhabit the contradiction, to make music in the unstable space between necessity and freedom.

So let us not abolish the bars, nor bow to them. Let us keep them in their place: scaffolding, not structure; approximation, not reality. The real music begins when the line spills past the line. The grid is there to resist. The lark is there to ascend.

Leave a Reply