1. The Problem of Time

In film, time is literal. Not an abstraction, not a metaphor, but measured seconds and frames. Cue 1 of Despiértame ran from 01:00:23:01 to 01:01:56:11: exactly 93.4 seconds. The music had to last the same.

At a chosen tempo of 120 BPM, each beat lasts half a second. Multiply it out and the cue spans 186.8 beats. In 4/4, that means 46 bars and 3.2 beats.

Here is the problem. Forty-six full bars give 92.0 seconds, short by 1.4 seconds. Forty-seven bars give 94.0 seconds, long by 0.6 seconds. Both miss the perceptual target.

The psychoacoustic window is narrow: sound may arrive up to 40 ms early, or up to 200 ms late, and still bind with the picture. Beyond that, the illusion fails. Neither 92.0 nor 94.0 falls inside the frame.

The solution was to end inside the bar itself. By cutting at the third beat of the 47th bar, the cue landed precisely at 93.4 seconds. What looked like overshoot or undershoot was corrected not by abandoning the tempo, but by choosing the exact beat to end on.

This is the contradiction: freedom of feel preserved, exactness solved by system.

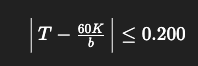

2. The Formula

The principle is simple.

Synchronization requires:

In words: Scene length ≈ (60 × number of beats) ÷ tempo (within 0.2 s).

That’s all. The math is trivial. But the mindset, treating synchronization as a solvable constraint, is rare.The calculation showed that whole bars could not fit the time. The decision to cut on a specific beat was the application of the formula to practice.

3. The Real Lesson

The arithmetic did not dictate the music. It guaranteed its security. The cue’s shape, 120 BPM, 4/4, continuous pulse, remained intact. The system solved the overshoot by designating the precise moment to end, not by breaking continuity.

This is the soil in which spontaneity can grow. The music was free to be expressive, even improvisatory, because the frame was solved in advance.

4. From Numbers to History

To modern eyes, this procedure may look strange: who calculates bars and beats so literally? Yet in two earlier traditions, eighteenth-century Naples and mid-twentieth-century Hollywood, this way of thinking was normal.

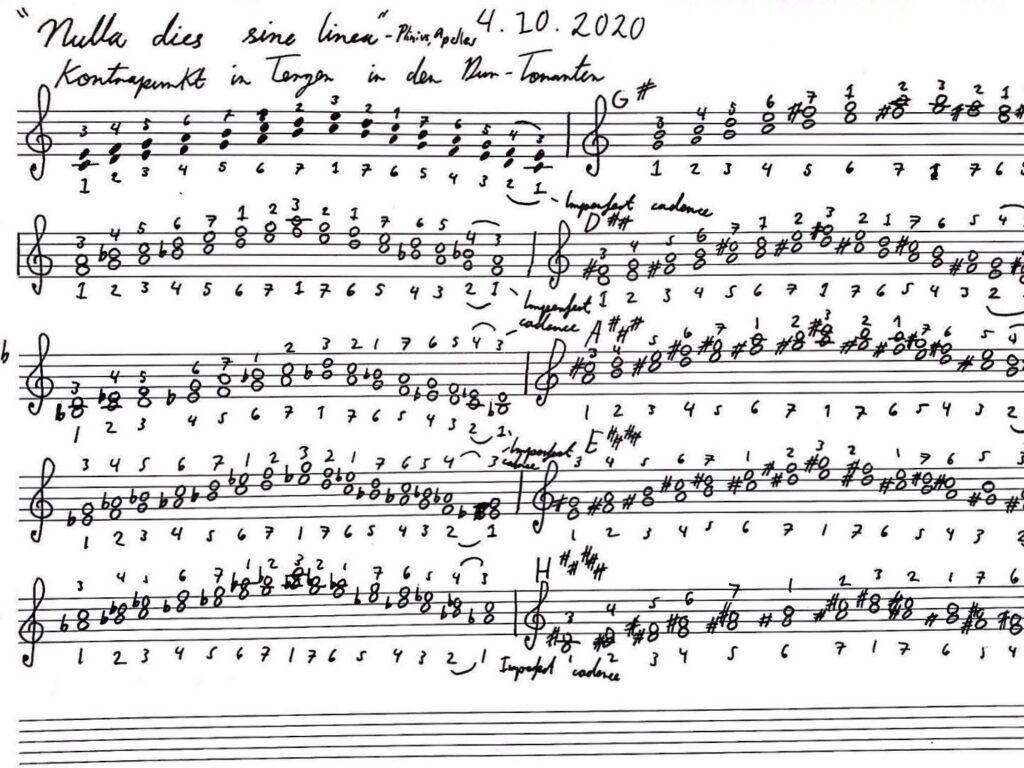

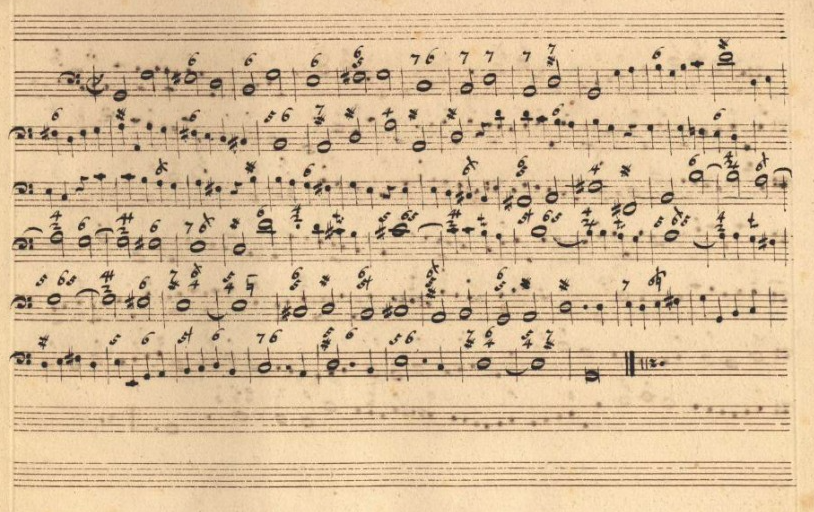

5. Naples: Skeleton Before Invention

In the Neapolitan conservatoires, composition was taught through partimento. Students did not begin with melody. They began with bass lines encoding harmonic direction. A partimento was a skeleton.

The lesson was that structure precedes invention. Once the skeleton was secure, counterpoint and melody could flower freely. The risk of collapse was removed at the start.

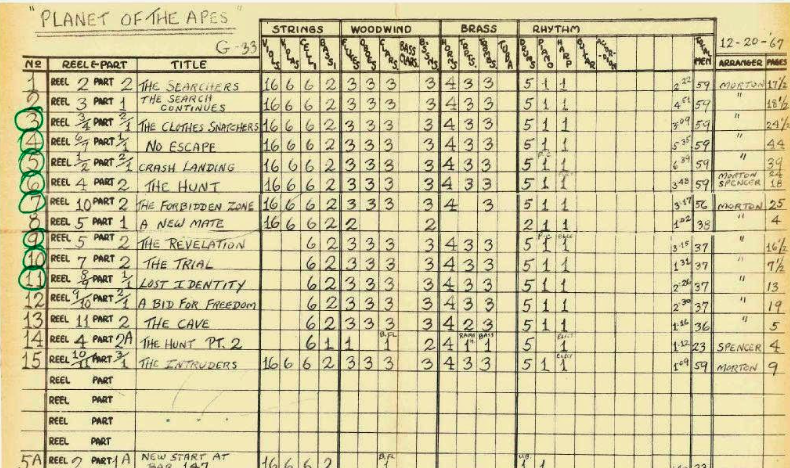

6. Hollywood: Math Before Melody

In mid-century Hollywood, film composers faced the same principle under different conditions.

With 35mm stock, arithmetic was unavoidable. Sixteen frames per foot; two-thirds of a second per foot. Click books turned frames into beats. Cue sheets and stopwatches provided scaffolding.

To synchronize a cue, the tempo and bar count were calculated. If the result was unmusical, a new calculation was made. Synchronization was never guessed. It was solved.

The lushness of Korngold, the drive of Herrmann, all rested on arithmetic foundations.

7. Today: The Abstraction Layer

The digital workstation has erased this necessity. Synchronization is now achieved through interface. A composer writes intuitively, drags the cue against the picture, and adjusts until the bars line up.

The equation still governs, but invisibly. The mindset shifts from parameter optimization to graphical manipulation.

This brings speed and flexibility. But it also produces a quiet form of deskilling. The connection between tempo, duration, and structure is no longer explicit. The knowledge of how survives. The knowledge of why is lost.

8. The Forgotten Soil

To return to this kind of arithmetic is not regression. It is recovery.

A melody launched without a scaffold risks collapse. A melody planted in a solved structure sings.

The lesson of Naples and Hollywood is the same: constraint is not the enemy of invention. It is its soil.

9. Why it Matters Now

This mindset is newly relevant.

- Film scores require continuity across many cues. Shared tempi create coherence.

- Interactive media requires adaptive music built on predefined rules.

- Generative systems are nothing but rules in action. Without scaffolds, they generate noise.

Constraint, once forgotten, becomes indispensable again.

10. Music as Thinking

Music is not only sound. It is also system.

To rediscover partimento is to rediscover harmony as schema. To recall Hollywood’s arithmetic is to recall time as solvable. Both show that music as thinking is less about spontaneity in chaos than about freedom within solved structures.

11. Conclusion

Between Naples and Hollywood lies a continuity worth remembering: skeleton before invention, math before melody. Both trained musicians to solve the frame before entering into expression.

Today’s digital tools hide that frame. But it remains available. The math is simple. The perceptual window is narrow. The freedom it grants is real.

Leave a Reply